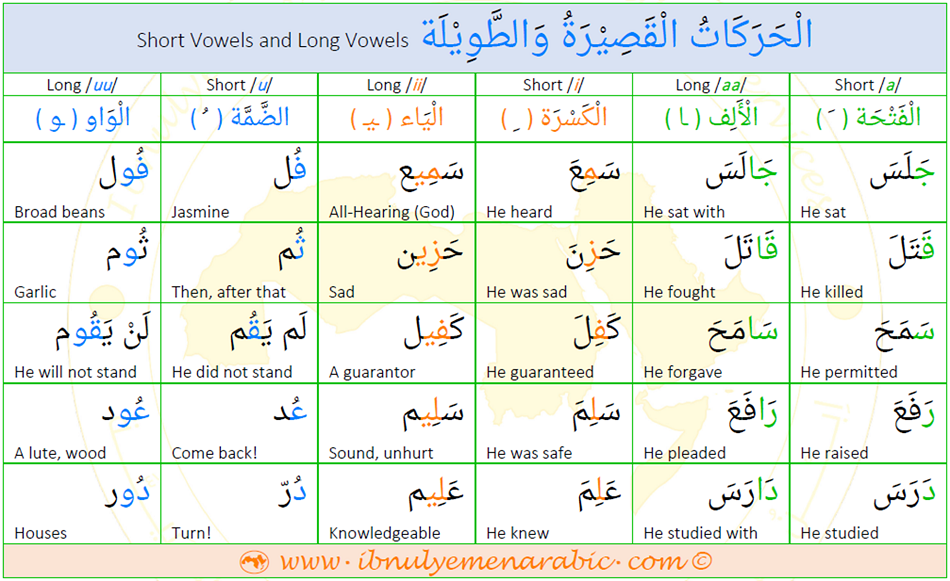

Vowels in Arabic are called harakat حَرَكَات, the singular of which is haraka حَرَكَة. Fortunately for the learners of Arabic as a foreign language, they are simple and limited. They are simple in that they are easily produced which makes the articulation of words straightforward. These vowels are [a], [i], and [u]; and for each short vowel, there is a corresponding long vowel. These are [aa], [ii], and [uu], respectively. So, there are six vowels in Arabic.

In Modern Standard Arabic (MSA) texts, such as news articles and books of general prose, short vowels are left out (i.e., not indicated). As a result, learners of the language as a foreign language encounter difficulties in reading and understanding these texts. For Arabs, such problems do not exist due to their linguistic intuition (i.e., knowledge of the language: grammar, word forms, and word meaning). So, for you, as a learner of Arabic as a foreign language, it is important that you learn the transparent Arabic (i.e., Arabic with short vowels) from the outset and until you build a sufficient linguistic knowledge of the language.

(1) Short Vowels:

(1) Short Vowels:The short vowels in Arabic are called الْحَرَكَاتُ الْقَصِيرَة. They are represented by three diacritical marks placed above or below the consonant that precedes them: the fatha, the kasra, and the dhamma. The fatha (ــَـ) is pronounced as [a]. The kasra (ــِـ) is pronounced as [i]. The dhamma (ــُـ) is pronounced as [u]. Therefore, they are secondary sounds that accompany letters. As stated above, these vowels are not written in MSA, but they are fully articulated. Put another way, although they seem additional, they are considerably essential. They determine the part of speech of the word, its function, and its meaning. For example, by changing the diacritical mark that accompanies the word علم, multiple words are generated: عَلِمَ 'he knew' is an active verb, عُلِمَ 'was known' is a passive verb, عِلْم 'science' is a noun, عَلَم 'flag' is a noun, عَلَّمَ 'to educate', among other words. Consequently, it is pedagogically essential that learners of Arabic as a foreign language learn how to add them to words from the outset of their learning. Now, let's look at each one them.

As can be seen from its shape, the fatha is a small alif (ا) lain down on the letter (this shape was proposed by the renowned Arab grammarian Al-Khalil ibn Ahmed Al-Farahidi in the 8th century). It is pronounced as [a], that is a reduced alif [aa]. At the word-level, it can determine the part of speech of words and may change word meanings.

|

رَجَعَ |

raja‘a |

He returned |

|

ذَكَرَ |

dhakara |

He mentioned |

|

جَمَعَ |

jama‘a |

He collected |

|

طَلَبَ |

Talaba |

He requested |

كَتَبَ |

kataba |

He wrote |

خَرَجَ |

kharaja |

He went out |

||

|

وَصَلَ |

waSala |

He arrived |

نَظَرَ |

naDHara |

He looked at |

رَقَدَ |

raqada |

He slept |

Proposed by Al-Farahidi in the 8th century, the kasra is a small alif (ا) laid down below the letter. It is put underneath the letter because it is the opposite of fatha. It is pronounced as [i], that is a reduced yaa [ii]. Like the fatha, it can determine the part of speech of the word and may change word meanings.

|

شَرِبَ |

shariba |

He drank |

|

سَمِعَ |

sami‘a |

He heard |

|

سَلِمَ |

salima |

He was safe |

|

سَهِرَ |

sahira |

He was awake |

ضَمِنَ |

dhamina |

He guaranteed |

حَزِنَ |

Hazina |

He was sad |

||

|

قَبِلَ |

qabila |

He accepted |

خَجِلَ |

khajila |

He was shy |

رَغِبَ |

raghiba |

He aspired |

The dhamma is a small waaw (و) added above the letter. It is pronounced as [u], that is a reduced waaw [uu]. Like the other two diacritical marks, it can determine the part of speech of words, and it may affect word meanings.

|

شُرِبَ |

shuriba |

was drunk |

|

ذُكِرَ |

dhukira |

was mentioned |

|

جُمِعَ |

jumi‘a |

was collected |

|

طُلِبَ |

Tuliba |

was requested |

كُتِبَ |

kutiba |

was written |

كَبُرَ |

kabura |

He grew up |

||

|

قُبِلَ |

qubila |

was accepted |

سُمِعَ |

sumi‘a |

was heard |

صَغُرَ |

Saghura |

He became small |

Long vowels in Arabic are called الْحَرَكَاتُ الطَّوِيلَة. They are represented by three letters that are saakina (i.e. have a sukuun/no vowel over them)—the alif, the yaa, and the waaw. The alif (ـا) is pronounced as [aa], the yaa (ـيـ) is pronounced as [ii], and the waaw (ـو) is pronounced as [uu]. In Arabic, these letters are also called weak letters (ِأَحْرُفُ الْعِلَّة) or the letters of prolongation (ِأَحْرُفُ الْمَدّ).

Pronounced as [aa], the alif ـا is a prolonged fatha, so it is called a long fatha. It is always saakina (i.e. has a sukuun/no vowel over it), and the letter that precedes it must have a fatha over it. So, given that it is always saakina and must be preceded by a letter that has a fatha over it, it never occurs at the start of words.

|

كَاتِب |

kaatib |

a writer |

|

قَالَ |

qaala |

He said |

|

مَقَال |

maqaal |

an article |

|

سَائِق |

saaʔiq |

a driver |

نَامَ |

naama |

He slept |

شَرَاب |

sharaab |

a drink |

||

|

شَاهِد |

shaahid |

a witness |

بَاعَ |

baa‘a |

He sold |

بَارِد |

baarid |

cold |

Pronounced as [ii], the yaa ـيـ is a prolonged kasra, so it is called a long kasra. Like the alif, it is always saakina (i.e. has a sukuun/no vowel over it), and the letter that precedes it must have a kasra below it. If the yaa occurs at the start of words, it is not a long vowel. It becomes a consonant, just like the y in 'yes.' In يَجْرِي yajrii, for example, the first يَـ is a consonant, while the final ي is a vowel.

|

خَبِير |

khabiir |

an expert |

|

بَعِيد |

ba‘iid |

far |

|

نَحِيف |

naHiif |

thin |

|

سَعِيد |

sa‘iid |

happy |

كَرِيم |

kariim |

generous |

غَرِيب |

ghariib |

strange |

||

|

جَمِيل |

jamiil |

beautiful |

فَقِير |

faqiir |

poor |

يَجْرِي |

yajrii |

He runs |

Pronounced as [uu], the waaw ـو is a prolonged dhamma, so it is called a long dhamma. Like the other two long vowels, it is always saakina (i.e. has a sukuun/no vowel over it), and the letter that precedes it must have a dhamma above it. Given that is it is saakina and the letter preceding it has a dhamma over it, it never occurs at the beginning of words. For example, in the word وُقُوف wuquuf 'stopping/standing,' the first وُ is mutaharrik (i.e., has a short vowel over it), so it is a consonant, namely w. The second و is saakin, so it is a long vowel.

|

ثُوم |

thuum |

garlic |

|

يَقُول |

yaquul |

He says |

|

خَرُوف |

kharuuf |

a sheep |

|

بُوق |

buuq |

a horn |

شُعُور |

shu‘uur |

feeling |

مَسْرُور |

masruur |

delighted |

||

|

نُور |

nuur |

light |

حُدُود |

Huduud |

borders |

لَيْمُون |

laymuun |

lemon |

In the following list, the words are minimal pairs (i.e., they differ only in the length of vowel). Besides the changes in pronunciation (from a short vowel to a long vowel), there is a change in meaning.

|

رَجَعَ |

raja‘a |

He returned |

|

رَاجَعَ |

raaja‘a |

He revised |

|

ذَكَرَ |

dhakara |

He mentioned |

ذَاكَرَ |

dhaakara |

He studied |

|

|

دَخَلَ |

dakhala |

He entered |

دَاخَلَ |

daakhala |

He interposed |

|

|

طَلَبَ |

Talaba |

He requested |

طَالَبَ |

Taalaba |

He demanded |

|

|

سَعَدَ |

sa‘ada |

He became happy |

سَاعَدَ |

saa‘ada |

He helped |

|

|

كَتَبَ |

kataba |

He wrote |

كَاتَبَ |

kaataba |

He wrote to |

The yaa is basically a long kasra. In the following list, in addition to the change in pronunciation, there is change in meaning.

|

حَزِن |

Hazin |

He was sad |

|

حَزِين |

Haziin |

Sad |

|

ضَمِن |

dhamin |

He guaranteed |

ضَمِين |

dhamiin |

A guarantor |

|

|

رَغِد |

raghid |

He was affluent |

رَغِيد |

raghiid |

Affluent |

|

|

سَلِم |

salim |

He was safe |

سَلِيم |

saliim |

Safe |

|

|

كَفِل |

kafil |

He guaranteed |

كَفِيل |

kaf iil |

A guarantor |

|

|

بَخِل |

bakhil |

He was stingy |

بَخِيل |

bakhiil |

Stingy |

The prolongation of dhamma results into a letter, that is a waaw which is pronounced as [uu]. This change in the length of sound can have some change in meaning, as in this list.

|

لَم يَعُد |

lam ya‘ud |

He didn't return |

|

يَعُود |

ya‘uud |

He comes back |

|

خَرُف |

kharuf |

He was senile |

خَرُوف |

kharuuf |

A sheep |

|

|

لَا تَخُنْ |

la takhun |

Do not betray |

تَخُون |

takhuun |

You betray |

|

|

لَا تَقُل |

la taqul |

Do not say |

لَنْ تَقُول |

lan taquul |

You will not say |

|

|

كُرَة |

kurah |

A ball |

كُورَة |

kuurah |

A county |

|

|

شُهِدَ |

shuhida |

was witnessed |

شُوهِدَ |

shuuhida |

was watched |

A diphthong is a sequence of two vowel sounds, that is a glide/movement from one sound to the next. In Arabic there are two dipthongs: ai/ay and au/aw. In both, the first vowel is a fatha, and second is either a yaa ي or a waaw و. Both يْ and وْ must be saakin (i.e., have a sukuun over them), as in بَيْت 'a house' سَيْف 'a sword', يَوْم 'a day', and ثَوْب 'a dress/garment.'

As explained earlier, the long vowels ي and و trigger a kasra below or a dhamma above the letter that precedes them, as in حَزِين and خَرُوف, respectively. If the letter that precedes them has a fatha, they become more like short vowels (namely, kasra /i/ and dhamma /u/) forming a diphthong with the fatha on the preceding letter: /ai/ (an in بَيْت) and /au/ (as in يَوْم).

|

ـَوْ au/aw |

ـَيْـ ai/ay |

||

|

جَوْلَة |

a round (match)/excursion |

جَيْب |

a pocket |

|

خَوْف |

fear |

دَيْر |

a monastery |

|

دَوْلَة |

a state/country |

ذَيْل |

a tail |

|

رَوْعَة |

splendor/beauty |

أَيْضًا |

too/also |

|

سَوْف |

will |

زَيْت |

oil |

|

شَوْق |

longing/eagerness |

خَيْر |

good (n) |

|

صَوْت |

sound/voice |

صَيْف |

summer |

|

فَوْقَ |

on/above |

ضَيْف |

a guest |

|

مَوْت |

death |

عَيْن |

an eye |

|

نَوْع |

a type/kind |

غَيْمَة |

a cloud |